Main Page

Interviews Menu

Alphabetical Menu

Chronological Menu

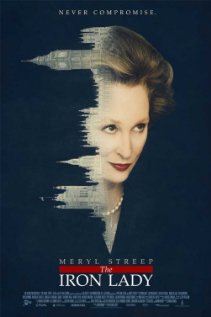

The Weinstein Company releases The Iron Lady December 30th, 2011 (limited) and wide on January 13th, 2012. NYC MOVIE GURU: Were you ever worried that the makeup hide your performance or, conversely, be your performance? Meryl Streep: in the process of developing the older Margaret, we ended up taking away, taking away, taking away. There were certain elements that the genius prosthetics designer, Mark Coulier, was able to achieve. He just created something that was tissue-thin, so I felt very free. I felt like I was looking at a member of my family, if not me. It actually made acting easier. NYC MOVIE GURU: How did your background in theater enhance your experience with The Iron Lady? Phyllida Loyd: We thought of the film as something of a ďKing LearĒ for girls ó a Shakespearean story, not a political story. Also, we spoke to a number of Margaret Thatcherís close associates who described her story in Shakespearean and operatic terms. I had worked in opera a lot, and to me, this did have some of the elements of a tragic opera. So yes, it was rather critical. Abi Morgan: I think the use of Denis ó in a way, like the Fool in ďKing LearĒ ó was obviously a theatrical device. I think the great thing about theater is that if you start in theater, it does build a confidence in poetic themes and ideas. So I suppose that was a great starting point in the script for me into thinking in a very poetic way. That affects the structure and the tone of the film. MS: I think for me to imagine myself in different ways comes from my beginnings in the theater. People are more accepting when you go apparently widely afield from who you are or where you were brought up. Otherwise, Iíd always be playing people from New Jersey which would limit my career. So yes, I felt like I had freedom to try to step into these very small, tight, big shoes. Harry Lloyd: I think it really helped when we were putting it together, the way we rehearsed it was very much like a play. We had all the scenes, and in every scene we went through, Phyllida kept it very loose, as you do in rehearsals. You donít try to pin it down, knowing youíve got a long way to go. Often in films, youíve got to rehearse it within five minutes, because youíve got to shoot it. We gave ourselves the time to play with it and work out in a scene, like, ďHow can we get you to do that dance?Ē So it was all very collaborative. I think a background in theater helps you work like that. NYC MOVIE GURU: How do you relate to Thatcher as a mother? MS: I had an inkling of the size of the day that she fulfilled. I looked at her daily calendar, and I tried to imagine that. Iím a mother, and I work in spurts throughout my career. Iíd work in four or five months and then not, so I was home a lot. She was unhappy if there were 10 minutes of free time anywhere in her day ó that was wasted time. So I imagined trying to be in the lives of your children to the degree that I tried to be in their lives. And I think it would have been very difficult. NYC MOVIE GURU: Why do you think itís so difficult for women to become leaders in politics? MS: Iím in awe of all the things that were arrayed against Thatcher succeeding, to get to the top of her party, and then to lead the country, and to be the longest-serving prime minister in the 20th century. The array of obstacles that stood before her in England at that time were enormous. I think she did a service to our team by getting there, even though you might not agree with the politics--just the fact that her determination, her stamina, her courage to take it on. I think anybody that stands up and is willing to be a leader who is prepared as she was and as smart as she was, itís admirable on a certain level, because you really sacrifice a great deal. All of our public figures do. NYC MOVIE GURU: Meryl, what do you think was the turning point for Margaret Thatcher in her decision to lead the life of a politician? What was the turning point for you in your own life when you decided that you wanted to make a living as an actress? MS: Iím sure that Margaret Thatcher was forged within her family, in a family of two girls, at a time when sons were favored, and a man that had no sons had no ambition, really ó no place to put his ambition. Her father was the mayor of Grantham, very engaged politically, but also he was a lay Methodist minister. He preached and he liked to be up front and speaking. And he discovered that of his two daughters, he had one that was uncommonly bright and uncommonly curious. And maybe this could be his boy. Thatís what I think, but I could be completely wrong. But I think in that time, it was a disappointment to have a family with only two girls, and it remains that disappointment in many parts of the world. So we can understand this. Itís not that alien of a landscape, although I canít imagine it. I think she fulfilled a promise. She was uncommonly curious, had a prodigious appetite for learning, for doing things right. And he infused in her the courage to get up and out. Not only is she the first female prime minister, but sheís also the first chemist to be elected prime minister. She took her degree in Oxford in chemistry, and then took the walk. I think she had lot of promise, and she wanted lived up to it. For me, I never really decided to become an actress. Iím still working on it. But no, being an actor lets me be a million different things, so I donít have to decide. NYC MOVIE GURU What kind of research did you do for The Iron Lady? Did you get to meet Margaret Thatcher? How much did you discover about her from the script or through your own personal observations? MS: I did observe lots of newsreel footage of her. The biggest challenge for me was just accomplishing the long lines of thought that she would launch into without taking a breath. Even with all the drama school that Iíve had, I had a lot of trouble managing that and matching to it. And that had something to do with who she was as a person ó just the galvanizing energy and the drive and the capacity to follow through with a conviction all the way to the end of your breath until you canít go any further, and not to let anybody interrupt her. It was masterful the way that she could manage these interviews. Iím taking notes on that. [laughs] AM: When you write about a political leader like this, obviously, she was surrounded by great correspondents, journalist and ministers. So there was the inevitable reading and watching broadcasts. When Phyllida came on, that was immense. But a lot of the time, I was digesting the material to throw it away because I wanted to not let it plague me or paralyze me because ultimately I think itís a creative process, and so youíre trying to almost trying to almost feel the imprint of a life rather to actually mirror it. So a lot of times, I was just reading and reading and reading, and I just put things down to see what settled and to see what events resonated and stayed with me. PL: The movie is a combination of very, very heavily politically fact-checked by people who were present in some of those scenes that we showed in the political world and then the world of pure imagination on Abiís part. So itís two very distinctive worlds. MS: I did not meet her. I did see her once at once at my daughterís university at Northwestern. We went to see her lecture, and that made an indelible impression on me, in about 2001 or 2002. I canít remember. NYC MOVIE GURU: Did you feel any added pressure or responsibility to make a movie about someone who is still alive, knowing that person could see the movie? MS: In regards to the special responsibility of playing someone who lives and could potentially see this, we have come under criticism for portraying a person who is frail and in delicate health. Some people have said that itís shameful to portray this part of a life. But the corollary to that is: If you think debility, dementia is shameful, if you think that the ebbing end of life is something that should be shut away, if you think that people need to be defended from those images, then yes, itís a shameful thing. But I donít think that. I have had experience with people with dementia. I understand it, and I think itís natural ó we are naturally interested in our leaders. And we tell stories about ourselves through the stories about important people. I mean, going back to ďKing LearĒ and deciding questions of existence through Hamlet. Weíre not talking about Hamletís politics or Lear was a good leader; weíre talking about the loss of power because itís interesting. Main Page Interviews Menu Alphabetical Menu Chronological Menu ______________________________________________________ |

The NYC Movie Guru

themovieguru101@yahoo.com

Privacy Policy