Main Page

Alphabetical Menu

Chronological Menu

|

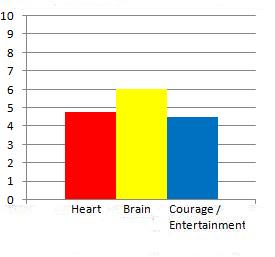

Agora  In Alexandria during the 4th Century A.D, Hypatia (Rachel Weisz), a philosopher/astronomer, teaches students at the Library of Alexandria which her father, Theon (Michael Lonsdale), runs. Two of her students, Orestes (Oscar Isaac) and, her slave, Davus (Max Minghella), flirt with her, but she refuses to flirt back with either of them. Davus, still in love with Hypatia, eventually joins the Christian fundamentalists who are staging a violent uprising against the Pagans. Meanwhile, Hypatia ponders whether Earth is flat or round, and desperately tries to prove that Earth revolves around the Sun rather than the Sun around the Earth. The mere suggestions of a heliocentric solar system back then was considered subversive, so Hypatia risks not only her livelihood, but also her life as she uses her intellect and reason instead of mere faith---not surprisingly, she does admit to being an atheist. Director/co-writer Alejandro Amenábar takes a very provocative premise and essentially squanders the opportunity to make it riveting or emotionally resonating for that matter because of a contrived screenplay that, no pun intended, goes around in circles while failing to breathe life into any of its characters. Moreover, there aren’t enough subtleties given that everything is pretty much force-fed to the audience with very little room for nuances. Rachel Weisz shines in the strong, charismatic performance which, fortunately, adds some much-needed gravitas to the film. However, Amenábar’s cinematography becomes rather pretentious and distracting because he includes too many aerial shots that swoop down from space all the way to Alexandria. Moreover, there aren’t enough many scenes end abruptly and awkwardly transition from one to the other because of choppy editing, so you never really get the chance to immerse yourself in any particular scene with the exception of the scene where Hypatia experiences a breakthrough when she draws in the sand the Earth revolves elliptically around the Sun. At a running time of 2 hours and 7 minutes, Agora is a tedious, choppily edited, uninvolving mess that can’t be saved by its provocative premise and Rachel Weisz’s radiant performance.  The Father of My Children   Mademoiselle Chambon   Micmacs  In French with subtitles. Bazil (Danny Boon) works as a video store clerk whose father was killed in a land mine accident back when he was a child. One night while at work, a stray bullet enters his head and gets lodged in there, nearly killing him. He loses his job and his apartment when he leaves the hospital. It turns out that the two military weapons corporations where the stray bullet and the land mine were manufactured happen to be located within the same city. Bazil now does everything in his abilities to exact revenge on the CEO’s of both companies, Marconi (Nicolas Marié) and Fenouillet (André Dussollier). He befriends a group of bizarre people who live beneath a junkyard, and persuades them to help him on his mission. The inventors include Buster (Dominique Pinon), a human cannonball, Elastic Girl (Julie Ferrier), a contortionist, Calculator (Marie-Julie Baup), a math whiz who’s capable of measuring anything just by using her brain, Tiny Pete (Michel Crémadès), an inventor, Remington (Omar Sy), an ethnographer, ex-con Slammer (Jean-Pierre Marielle), and Mama Chow (Yolande Moreau), the group’s matriarch. None of the details of their adventures together will be spoiled here, but it’s worth noting that their revenge tactics are outrageously funny, twisted and very clever. Director/co-writer Jean-Pierre Jeunet has a knack for coming up with brilliantly bizarre visual gags, dark humor and eccentric characters which you’ll find in abundance here. Keep in mind, though, that the hilarious scenes come at you at such a fast rate that you may not notice all of them while other might go over your head because they’re lost in translation. Not surprisingly, Jeunet fills Micmacs with stylish cinematography, visual effects and set designs that provide plenty of eye candy. Many of the comedic sequences veer toward silliness and require a heavy dose of suspension of disbelief, but there’s never a dull moment to be found. At a running time of 1 hour and 44 minutes, Micmacs is wildly imaginative, outrageously funny, daring, delightfully twisted and filled with eye-popping visual panache.  Picasso and Braque Go to the Movies  This informative and engaging documentary, narrated by Martin Scorsese, focuses on how the birth of cinema during the turn of the 20th Century influenced the artworks of world-renowned painters Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. Both Picasso and Braque were film buffs fascinated by the magic of the moving image which, at the time, was considered groundbreaking and revolutionary. The films of Georges Méliès with all of their nifty special effects had an impact on the way that Picasso painting his Cubist paintings. Upon his attendance at the Exposition Universelle of 1900 in Paris, Picasso became entranced when he watch a film entitled The Serpentine Dance by the Lumiere brothers where Loie Fuller danced wearing veils that, from the viewer’s perspective, changed color repeatedly. Interestingly, back then, the advances in cinematography didn’t allow for the simple special effects of changing the colors, so the changes occurred through lighting and by the filmmakers playing around the film stock itself. Picasso’s Cubist paintings reflect his admiration for the movement of the veils in that particular film. In 1907, Picasso and Braque met and become very good friends. Not surprisingly, some of their Cubist paintings look similar at first glance, but there are still nonetheless differences between the two that are worth taking notice of. Director Arne Glimcher combines insightful interviews with artists, namely, Chuck Close, Julian Schnabel, Robert Whitman, Lucas Samaras and Eric Fischl, along with footage from the films that influenced Picasso and Braque’s works of art. Glimcher’s thesis about the connection between the birth of film and Cubism is certainly a fascinating one and she includes a wealthy of information and keen observations to support her thesis. However, what ever-so-slightly diminishes the film’s provocativeness toward the end, though, is its lack of an interesting conclusion that ties everything together through more thorough analysis while further exploring the most important question that every documentary ought to answer in some fashion: “So what?” At a very brief running time of 1 hour and 2 minutes, Picasso and Braque Go to the Movies manages to be an informative, well-edited and engaging documentary that needs a more thorough and provocative conclusion.   Survival of the Dead   Main Page Alphabetical Menu Chronological Menu ______________________________________________________ |

The NYC Movie Guru

themovieguru101@yahoo.com

Privacy Policy